The Changing Face of Masculinity in Cinema

As Seen Through “The Hero’s Journey” in The Incredibles

In 1949, Joseph Campbell first released his influential book concerning comparative mythology, entitled The Hero with a Thousand Faces, in which he unfolds his theories about narratives and archetypes. Campbell contends that most myths and stories adhere to a basic structure, called the monomyth, and have similar characters. The author famously summarizes his thoughts on the monomyth when he writes early on in the book, “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man” (Campbell, 2008, p. 23). Since its publication, Campbell’s work has been applied to numerous storytelling vehicles, including literature and film, and has been adapted by other scholars.

One such scholar is Christopher Vogler. In the early-1980s, the writer stumbled upon Campbell’s work and began to recognize Campbell’s mythological story patterns to be present in movies as well, particularly in the Star Wars films. A few years later, while working as a story consultant for Walt Disney Pictures, Vogler sent out a seven page memo outlining his summation of Campbell’s ideas and how they truly were present in modern films. The memo circulated the Hollywood industry like wildfire and Vogler was reassigned by Disney legend Jeffrey Katzenberg to the Animation division where he began work on many of what are now considered the animation classics of our time, all while applying his formulation of Campbell’s theories. (Vogler, 2011). In the early-1990s, after much encouragement from his industry peers, Vogler adapted Campbell’s work into a textbook, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, to great acclaim. It was Vogler’s textbook which played a major role in popularizing the phrase “The Hero’s Journey” when describing a narrative pattern similar to the monomyth that Campbell described. In Vogler’s formulation of “The Hero’s Journey,” the Hero passes through twelve stages and there eight basic character archetypes encountered. This is compared to Campbell’s seventeen stages, although both authors admit that not every myth or story would contain every single one of their stages.

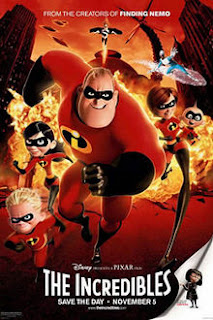

Pixar Animation Studios, a branch of Walt Disney films, continues the organization’s history of producing classic films which appeal to audience members of every demographic utilizing “The Hero’s Journey.” Mark Seton describes Pixar as “a company where embodiment, debate, improvisation and lived experience are as valued as technical prowess” (Steton, 2008, p. 94). In other words, Pixar creators try to give an aura of real-life authenticity to their movies. One such film is the hit computer-animated, action-comedy film, “The Incredibles,” released in 2004 under the direction of Brad Bird. The film grossed over $70 million its opening weekend in the United States, which at its time was the highest opening weekend gross for a Pixar film, the highest opening weekend for a non-sequel animated feature, and the highest opening weekend for a non-franchise-based film. It was also the number one movie the following weekend, making over $50 million, and went on to gross over $631 million worldwide. It was nominated for four Academy Awards, including “Best Original Screenplay,” and won two of those, including “Best Animated Feature.” It also won the Golden Globe for “Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.” (IMDb).

The first stage of “The Hero’s Journey” is “The Ordinary World,” in which the audience first hears about or sees the world in which the Hero lives before the story begins. The Hero, uneasy, uncomfortable or unaware, is introduced sympathetically so the audience can identify with the situation or dilemma. By influencing the audience to identify with the Hero and the situation, the storyteller ensures that the audience is emotionally invested in the story. In this stage the storyteller captures audience attention and interest. This identification and investment is achieved by showing the Hero against a background of environment, heredity, and personal history. There is an obvious sort of polarity in the Hero’s life which is pulling in different directions and causing stress. (Vogler 2007).

This stage in “The Incredibles” is depicted in the initial scenes and introductory montage. The audience is introduced to a world filled with individuals with fantastic abilities, known as “superheroes” or “supers,” for short. These supers protect average citizens from “super-villains” and natural disasters. This is the “Ordinary World” in which we find the film’s central protagonist, Bob Parr, a particularly powerful super himself who goes by the name, “Mr. Incredible.” We also meet “Elastigirl,” whom Bob marries, and the audience is given information concerning their respective opinions concerning the balance between being a super and maintaining a family. (Bird, 2004). Audience members are expected to relate to the struggle in striking a balance between a home life and outside responsibilities. In this stage, the film introduces audience members to the world of supers and invests them in the film’s main characters by depicting them as having relatively ordinary lives and problems, despite their extra-ordinary abilities.

This is to be especially relatable for the men watching the film, as the “Ordinary World” of the supers is introduced as a rather masculine one in which villains are defeated through the work of one individual who is determined, assertive, and strong. In his book, An Introduction to Masculinities, author Jack Kahn defines masculinity “as the complex cognitive, behavioral, emotional, expressive, psychosocial, and sociocultural experience of identifying with being male,” and says, “that there are multiple ways in which people may experience the world of masculinity” (Kahn, 2009, p. 2). The various ways in which one experiences identifying with being male is reflected throughout cinema and has presented an evolution in how that masculinity is depicted in theaters. “Iconic Masculinities, Popular Cinema and Globalization” is a study of cinematic masculinity by David Hansen-Miller which states that “the exaggerated masculinity of the Hollywood action hero in the eighties and nineties has given way to somewhat more complicated characters… the moral basis for action has shifted to the family” (Hansen-Miller, 2010, p. 34, 37).

The character arch of Bob through “The Incredibles” film exemplifies and serves as a meta-narrative for this emerging emasculation of male action heroes. In “Post-Princess Models of Gender: The New Man in Disney Pixar,” authors Ken Gillam and Shannon Wooden detail the shift in animation films from those with female main characters and stereotypically masculine minor characters to those with male main characters who struggle with masculinity. Pixar in particular they say, “consistently promotes a new model of masculinity, one that matures into acceptance of its more traditionally ‘feminine’ aspects” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 2). In describing Bob’s emasculating fall from power from which he only returns with the help of females, they discuss the character we see before he begins this arch. “An old-school superhero, Mr. Incredible opens The Incredibles by displaying the tremendous physical strength that enables him to stop speeding trains, crash through buildings, and keep the city safe from criminals. But he too suffers from the emotional isolation of the alpha male… He communicates primarily through verbal assertions of power… and limits to anger and frustration the emotions apparently available to men” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 4).

The character of Bob clearly represents the changing face of masculinity at the movies. The creators use the “Ordinary World” stage, to not only introduce viewers to a world filled with heroes who have superhuman capabilities and interpersonal struggles, but to also introduce us to a film character we think we are familiar with. Yet as the film progresses through the rest of Vogler’s stages, the audience will begin to see a shift in the masculinity of Bob.

The second stage of Vogler’s structure is “The Call to Adventure,” in which the hero is presented with a problem, challenge, or adventure. In other words, something occurs that impacts or changes the situation or environment of the Hero’s “Ordinary World.” This can originate either from external pressures or from an internal conflict which rises up from deep within the Hero and forces him to face the beginnings of change. This stage is what begins to turn the wheels which set the Hero’s adventure in motion and is a critical and essential step in creating a story. (Vogler, 2011b).

In “The Incredibles,” this stage manifests itself in the scene in which Mr. Incredible saves the life of a man attempting to commit suicide. In the rescue the saved man is injured and subsequently files a lawsuit against Mr. Incredible and the government of the United States which provides backing for the nation’s supers. This launches an onslaught of additional lawsuits against supers, political protests, and the eventual passage of a law outlawing the practice of being a super. Those who once protected the populace with their abilities are forced into hiding and must live their lives under the guise of being average citizens. Herein lays “The Call to Adventure,” in the forced retirement and disempowerment of all supers.

Ironically, this emasculating forced retirement is the result of the masculinity of the supers themselves. It was because of Mr. Incredible’s tendency to accomplish task as physically as possible, expected of such a masculine character, which led to the lawsuit in the first place. As Gillam and Wooden state, “Mr. Incredible is perhaps the most obviously disempowered: despite his superheroic feats, Mr. Incredible has been unable to keep the city safe from his own clumsy brute force” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 4). The oppression of supers, which prevents them from using their powers, points not only to behavior modification, but also to the emasculating suppression of the supers’ identity and purpose. This is the initial and overpowering obstacle which is faced by all supers. The difficult balance between the ordinary parts of life and the extraordinary, hinted at in the “Ordinary World” stage, is suddenly up-heaved, leaving Bob feeling overwhelmed by the crushing hegemony of the ordinary life he is surrounded by. Forced retirement, the suppression of his identity, is the obstacle which disrupts the Hero’s “Ordinary World” and Bob’s attempts to conquer it ultimately serve as the catalyst for the rest of the film’s adventures. (Bird, 2004).

The “Refusal of the Call” is Vogler’s third stage, in which the Hero refuses the challenge or journey. Usually, according to Vogler, this is because the Hero is afraid of the unknown, which leads to the Hero trying to turn away from the adventure, however briefly. Alternatively in some cases, another character may express the uncertainty and danger ahead. This stage creates internal conflict concerning the physical quest that lies before the Hero. This contributes to the growing suspense of the story, which is partially relieved when the Hero finally takes up the challenge of the adventure. It also reinforces the familiarity of the Hero as someone who struggles with important decisions just like everyone else. Being too vigorous in taking on the adventure could often seem unrealistic in the mind of the audience and therefore decrease the validity of the story. (Vogler, 2007).

This stage in “The Incredibles” is shown as Bob, despite the energetic encouragement from his wife to suppress his desire to use his abilities and hold down a normal job, reunites with his old super friend, Frozone, to save people from a burning building. Bob’s resistance to being fully ordinary can also be seen at his job at an insurance agency where continues to try to help people by educating an elderly woman concerning the loopholes she can take advantage of in her plan. More obviously it is seen when Bob throws his boss through a number of walls after the boss prevents Bob from stopping a crime. Bob even vocalizes his discontent when he argues with his wife that their son who has super speed, Dash, should be allowed to showcase his abilities by playing sports. These are all clear examples of Bob seeking rebellion against the disruption of the “Ordinary World,” the oppression of being a super, with open displays of power. Bob wishes he could pretend that he still lived in the “Ordinary World,” where he was free to use his abilities. (Bird, 2004). Ironically, Bob’s rebellious refusal to compromise concerning his masculine actions only leads to further emasculation. “To add insult to injury, Mr. Incredible’s diminutive boss fires him from his job… and his wife, the former Elastigirl, assumes the ‘pants’ of the family” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 4).

Another stage is “Meeting the Mentor,” in which the Hero meets a mentor to gain advice or training for the adventure. This mentor is often a seasoned traveler of the worlds who gives the Hero training, equipment, or advice that will help on the journey. However, sometimes this stage can manifest itself as the Hero simply reaching within to a source of courage and wisdom. (Vogler, 2011b). This stage in “The Incredibles” is the introduction of the character Edna Mode, a famous fashion designer who used to design suits for the supers. As such, she is well versed within the realm of supers and their abilities. This certainly contributes to her being thought of as a seasoned veteran. For Bob, Edna furnishes a brand new super suit which he utilizes as he begins to reassume his super persona after being hired by a mysterious woman to stop a destructive robot on her company’s island. Additionally, Edna creates super suits for the rest of Bob’s family, who later in the film use them as they too begin to use their powers. Here we see the seasoned veteran providing the Heroes with the tools they need to be successful. Lastly, it is Edna who advises Helen, Bob’s wife, to follow her husband to the island after she begins to suspect that Bob may be returning to being a super. (Bird, 2004).

“Crossing the Threshold” is another stage in which the Hero leaves the “Ordinary World” and goes into the “Special World.” This most commonly occurs at the end of Act One, when the Hero commits to leaving the “Ordinary World” and entering a new region or condition with unfamiliar rules and values. (Vogler, 2007). We see this stage occurring in scenes in which Bob has tried to put aside what super-masculine role he believes is expected of him to settle down into a normal, ability-free life with an average job. It is present in those first moments when there are no open displays of power. Even when Bob rebelliously uses his powers with Frozone to save people from a burning building, they wear ski masks to hide their citizen identities and their super identities. These are Bob’s first attempts at suppressing his masculine identity as a super and hiding his displays of power from the world. (Bird, 2004).

The sixth stage is called “Tests, Allies, and Enemies.” In this stage, the Hero faces tests, meets allies, confronts enemies, and learns the rules of the “Special World.” In other words, the Hero is discovering his place outside of the “Ordinary World” and is sorting out his allegiances in the “Special World.” (Vogler, 2007). Bob certainly does this in “The Incredibles.” The most influential character that he meets is Mirage, the mysterious woman who encourages Bob to reassume in secret his role as Mr. Incredible. Bob also faces tests in battling the robot on the island, as well as in hiding his activities from others. Finally, Bob encounters Syndrome, the film’s main antagonist. Ironically enough, both Syndrome and Bob share the desire to return to the “Ordinary World,” in which supers live in the open. Although, while Bob wants to help people while simultaneously adding a extraordinary counterbalance to the ordinary things in his life, Syndrome motivations are more concerned with his own renown and glorification. (Bird, 2004).

Another stage is the “Approach” stage, in which the hero hits setbacks during tests and may need to try a new idea.” This describes how the Hero and his newfound Allies prepare for the major challenge in the Special World. (Vogler, 2007). For Bob, preparation for the major challenge occurs as he begins to reassume super activities. However, setbacks arise when Syndrome reveals himself and Bob barely escapes Syndrome’s newly upgraded robot. He makes his way back into Syndrome’s lair, only to be captured. For Helen and two of their children, setbacks occur when Helen begins to suspect that Bob has reassumed his super activities and when, as they travel to the island, their plane is shot down. This is also an emotional setback for Bob, to whom Syndrome reveals the shooting down of the plane. Yet the attack on the plane, in combination with the use of their new super suits and the evasion of guards, actually helps the family prepare for the major challenge. (Bird, 2004). It is in this stage that Bob begins to “embrace his own dependence, both physical and emotional. Trapped on the island of Chronos, at the mercy of Syndrome, … Mr. Incredible needs women – his wife’s superpowers and Mirage’s guilty intervention to escape” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 6). This embrace of the more feminine attribute of dependence also helps Bob prepare for the climax ahead.

“The Ordeal” is one of the more exciting stages, as it is the biggest life or death crisis. This occurs near the middle of the story, as the Hero enters a central space in the “Special World” and confronts death or faces his or her greatest fear. Often during this scene, out of the moment of death comes a new life. (Vogler, 2007). In “The Incredibles,” this stage occurs on the island in the rescue of Mr. Incredible and the family’s battle to escape from the island. During this challenge each of the characters learn even more about their powers and learn how to work together as a team. Their escape is an epic fight against the minions of Syndrome and the lives of each character are certainly in danger, forcing them to confront fears of death and also Bob’s fear of losing his family. In working together for the first time, the characters realize the strength of their family bonds and by the end of the scene we see the “birth” of the Incredibles as a unit, as opposed to separate individuals. (Bird, 2004). This initial success through teamwork foreshadows the ultimate shift in from independent masculinity that Mr. Incredible encounters later in the film.

“The Ordeal” leads to the realization of “The Reward,” in which the Hero takes possession of the treasure won as a result of surviving death and overcoming fear. Vogler describes how there may be a celebration, but there is also the danger of losing the treasure again. (Vogler, 2007). “The Rewards” gained by the Incredibles is safety the reunion of the family. After escaping the island, there are no longer any forces keeping them apart or endangering them specifically. Additionally, Bob has achieved his “Reward” of being a super once again. However, despite joy in their victory, the Incredibles can take little time to celebrate, as Syndrome has released his robot upon civilization. (Bird, 2004).

This leads to the stage called “The Road Back,” in which the Hero must return to the “Ordinary World.” This normally, according to Vogler, occurs three-fourths of the way through the story as the Hero is driven to complete the adventure; leaving the Special World to be sure the treasure is brought home. Vogler points out that often a chase scene signifies the urgency and danger of the mission. (Vogler, 2007). This is a stage clearly apparent in “The Incredibles,” as the family rushes back to society in order to save lives from the actions of Syndrome and his robot. (Bird, 2004).

Once back in the city, the Incredibles face “The Resurrection,” Vogler’s stage in which the Hero faces death and is forced to use everything he has learned. In other words, it is a climax at which the Hero is severely tested once more on the threshold of home. Often, the Hero is purified by a last sacrifice, another moment of death and rebirth, but on a higher and more complete level. By the Hero’s actions, the polarities that were in conflict at the beginning are finally resolved. (Vogler, 2007). In “The Resurrection” stage, the Incredibles each have to use their newly developed skills, including working together as a team and utilizing information learned in their adventures, in order to defeat Syndrome’s robot. As Vogler describes, this scene happens in the home city of the family. (Bird, 2004).

Mr. Incredible’s ultimate realization that he can no longer succeed on his own, but now needs others, contributes to his final shift in masculinity. “To overpower the monster Syndrome has unleashed on the city, and to achieve the pinnacle of the New Man model, he must also admit to his emotional dependence on his wife and children” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 6). Mr. Incredible makes one last attempt to refuse his emasculation by hiding his family in a bus, but even his confessed reasons for doing so have altered. He lovingly admits to Elastigirl that “I can’t stand to lose you again,” which stands in sharp contrast with is ideology at the start of the movie: “I work alone” (Bird, 2004). However, his family does not stay hidden for long; he needs them to finally vanquish the robot. Yet when the robot is destroyed, so too are “any vestiges of the alpha model, as the combined forces of the Incredible family locate a new model of postfeminist strength in the family as a whole. This communal strength is not simply physical but marked by cooperation, selflessness, and intelligence. The children learn that their best contributions protect the others” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 6). Thusly Bob completes his character arch, reflective of the shifting face of masculinity in cinema. As Hansen-Miller says, “While the hero can be traumatized by the burden of their abilities and the sources of their power they are ultimately heroic and justified by reassigning those abilities to a fight for heterosexual love and family” (Hansen-Miller, 2010, p. 38).

The “Return with the Elixir” stage describes the Hero’s return home from the journey where he uses the “Elixir” to help everyone in the “Ordinary World.” Vogler details how often the transformation of the “Ordinary World” as a result of the “Elixir” often mimics the transformation that the Hero has undergone throughout his adventure. In “The Incredibles,” the return of supers and their abilities is the “Elixir” that is presented to the “Ordinary World.” Just as Bob realizes how important his family is to him, the people of the city, whom they have saved, realize how important the supers are to them and their city. (Bird, 2004).

In summation, Bob is a super living in an “Ordinary World,” in which supers are respected and appreciated and he, as Mr. Incredible, can accomplish great displays of power, which provide for him an extraordinary counterbalance to the ordinary things in his life. However, the forced retirement of supers creates a “Special World” in which supers cannot be heroes who accomplish great things. This is a “Call to Adventure,” as it represents a direct challenge to Bob’s identity and purpose. Bob initially “Crosses the Threshold” into this “Special World” and lives the stereotypical American Dream, with a steady job and no phenomenal feats of strength. However, Bob “Refuses the Call” to retire and secretly, yet defiantly, takes part in displays of power. Bob’s struggle to overcome what he perceives as the suppression of the “Special World” brings him into contact with Edna, a “Mentor” who prepares him for the resumption of super work, and Mirage, an “Ally/Enemy who provides him with the opportunities of “Tests” through which he can be a super once more. The “Approach” to the film’s climax involves Bob being captured by Syndrome, an “Enemy,” and the rest of the Incredible family making their way to the island to find Bob. In the “Ordeal,” Bob is rescued and the family escapes the island, learning about their powers and how to work together along the way, and they achieve the “Rewards” of being reunited as a family and being able to reach their potential as supers. Yet they quickly take the “Road Back” in order to defeat Syndrome’s robot in the “Resurrection” stage, in which they must use everything they learned along the way in order to succeed. This leads to their “Return with the Elixir,” which manifests itself in the film as the return of the supers and their abilities, and also to the return of the “Ordinary World,” in which the story began.

Using “The Hero’s Journey,” the creators also presented an insightful look into the changing face of masculinity in the cinema. Bob starts the film reflective of the classical masculine heroes of the eighties and nineties. However, his masculinity that was once so applauded eventually led to his emasculating downfall. In order to reestablish himself as a super, Bob ultimately renegotiated his masculinity as he was forced to accept the help of others, including women. However, this is a role that Bob finally accepts and it is viewed as a more ideal form of masculinity than that with which Bob began the film. This shift in cinematic masculinity, represented in “The Incredibles” by Bob, is explained by Hansen-Miller when he states that “the attempt to reconstruct masculinity outside of historical homosocial value systems indicates recognition of female audiences and agency” (Hansen-Miller, 2010, p. 38). Gillam and Wooden concur, saying “The trend of the New Man seems neither insidious nor nefarious, nor is it out of step with the larger cultural movement. It is good… to be aware of the many sides of human existence, regardless of traditional gender stereotypes. However, maintaining a critical consciousness of the many lessons taught by [movies]… remains a necessary and ongoing task… for all conscientious cultural critics” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 7).

“The Incredibles” certainly offers itself for such analysis, as it effectively uses “The Hero’s Journey” to provide a clear example of the changing face of masculinity in film.

Works Cited

Bird, Brad (Director). (2004). The Incredibles [Motion Picture]. United States: Pixar Animation Studios.

Campbell, Joseph. (2008). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gillam, Ken, & Wooden, Shannon R. (2008). Post-Princess Models of Gender: The New Man in Disney/Pixar. Journal of Popular Film & Television, 36(1), 2-8. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

Hansen-Miller, David. (2010). “Iconic masculinities, popular cinema and globalization.” Media Development, 57(1), 33-38. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

“The Hero’s Journey.” ThinkQuest. (2011). Retrieved from <http://library.thinkquest.org/03oct/00800/journey.htm>.

“The Incredibles.” IMDb. (2011). Retrieved from <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0317705/>.

Kahn, Jack S. (2009). An Introduction to Masculinities. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Seton, M. (2008). Pixar Phenomenology: The Embodiment of Animation. (cover story). Metro, (157), 94-97. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

Vogler, Christopher. (2007). The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Vogler, Christopher. (2011a). “A Practical Guide to Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces.” The Writer’s Journey. Retrieved from <http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero%27s_journey.htm#Practical>.

Vogler, Christopher. (2011b). “The Hero’s Journey Outline.” The Writer’s Journey. Retrieved from <http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero%27s_journey.htm#Hero>.

Vogler, Christopher. (2011c). “The Heroine’s Journey/Archetypes.” The Writer’s Journal. Retrieved from <http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero%27s_journey.htm#Heroine>.

Vogler, Christopher. (2011d). “The Memo that Started it All.” The Writer’s Journey. Retrieved from <http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero%27s_journey.htm#Memo>.

The first stage of “The Hero’s Journey” is “The Ordinary World,” in which the audience first hears about or sees the world in which the Hero lives before the story begins. The Hero, uneasy, uncomfortable or unaware, is introduced sympathetically so the audience can identify with the situation or dilemma. By influencing the audience to identify with the Hero and the situation, the storyteller ensures that the audience is emotionally invested in the story. In this stage the storyteller captures audience attention and interest. This identification and investment is achieved by showing the Hero against a background of environment, heredity, and personal history. There is an obvious sort of polarity in the Hero’s life which is pulling in different directions and causing stress. (Vogler 2007).

This stage in “The Incredibles” is depicted in the initial scenes and introductory montage. The audience is introduced to a world filled with individuals with fantastic abilities, known as “superheroes” or “supers,” for short. These supers protect average citizens from “super-villains” and natural disasters. This is the “Ordinary World” in which we find the film’s central protagonist, Bob Parr, a particularly powerful super himself who goes by the name, “Mr. Incredible.” We also meet “Elastigirl,” whom Bob marries, and the audience is given information concerning their respective opinions concerning the balance between being a super and maintaining a family. (Bird, 2004). Audience members are expected to relate to the struggle in striking a balance between a home life and outside responsibilities. In this stage, the film introduces audience members to the world of supers and invests them in the film’s main characters by depicting them as having relatively ordinary lives and problems, despite their extra-ordinary abilities.

This is to be especially relatable for the men watching the film, as the “Ordinary World” of the supers is introduced as a rather masculine one in which villains are defeated through the work of one individual who is determined, assertive, and strong. In his book, An Introduction to Masculinities, author Jack Kahn defines masculinity “as the complex cognitive, behavioral, emotional, expressive, psychosocial, and sociocultural experience of identifying with being male,” and says, “that there are multiple ways in which people may experience the world of masculinity” (Kahn, 2009, p. 2). The various ways in which one experiences identifying with being male is reflected throughout cinema and has presented an evolution in how that masculinity is depicted in theaters. “Iconic Masculinities, Popular Cinema and Globalization” is a study of cinematic masculinity by David Hansen-Miller which states that “the exaggerated masculinity of the Hollywood action hero in the eighties and nineties has given way to somewhat more complicated characters… the moral basis for action has shifted to the family” (Hansen-Miller, 2010, p. 34, 37).

The character arch of Bob through “The Incredibles” film exemplifies and serves as a meta-narrative for this emerging emasculation of male action heroes. In “Post-Princess Models of Gender: The New Man in Disney Pixar,” authors Ken Gillam and Shannon Wooden detail the shift in animation films from those with female main characters and stereotypically masculine minor characters to those with male main characters who struggle with masculinity. Pixar in particular they say, “consistently promotes a new model of masculinity, one that matures into acceptance of its more traditionally ‘feminine’ aspects” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 2). In describing Bob’s emasculating fall from power from which he only returns with the help of females, they discuss the character we see before he begins this arch. “An old-school superhero, Mr. Incredible opens The Incredibles by displaying the tremendous physical strength that enables him to stop speeding trains, crash through buildings, and keep the city safe from criminals. But he too suffers from the emotional isolation of the alpha male… He communicates primarily through verbal assertions of power… and limits to anger and frustration the emotions apparently available to men” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 4).

The character of Bob clearly represents the changing face of masculinity at the movies. The creators use the “Ordinary World” stage, to not only introduce viewers to a world filled with heroes who have superhuman capabilities and interpersonal struggles, but to also introduce us to a film character we think we are familiar with. Yet as the film progresses through the rest of Vogler’s stages, the audience will begin to see a shift in the masculinity of Bob.

The second stage of Vogler’s structure is “The Call to Adventure,” in which the hero is presented with a problem, challenge, or adventure. In other words, something occurs that impacts or changes the situation or environment of the Hero’s “Ordinary World.” This can originate either from external pressures or from an internal conflict which rises up from deep within the Hero and forces him to face the beginnings of change. This stage is what begins to turn the wheels which set the Hero’s adventure in motion and is a critical and essential step in creating a story. (Vogler, 2011b).

In “The Incredibles,” this stage manifests itself in the scene in which Mr. Incredible saves the life of a man attempting to commit suicide. In the rescue the saved man is injured and subsequently files a lawsuit against Mr. Incredible and the government of the United States which provides backing for the nation’s supers. This launches an onslaught of additional lawsuits against supers, political protests, and the eventual passage of a law outlawing the practice of being a super. Those who once protected the populace with their abilities are forced into hiding and must live their lives under the guise of being average citizens. Herein lays “The Call to Adventure,” in the forced retirement and disempowerment of all supers.

Ironically, this emasculating forced retirement is the result of the masculinity of the supers themselves. It was because of Mr. Incredible’s tendency to accomplish task as physically as possible, expected of such a masculine character, which led to the lawsuit in the first place. As Gillam and Wooden state, “Mr. Incredible is perhaps the most obviously disempowered: despite his superheroic feats, Mr. Incredible has been unable to keep the city safe from his own clumsy brute force” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 4). The oppression of supers, which prevents them from using their powers, points not only to behavior modification, but also to the emasculating suppression of the supers’ identity and purpose. This is the initial and overpowering obstacle which is faced by all supers. The difficult balance between the ordinary parts of life and the extraordinary, hinted at in the “Ordinary World” stage, is suddenly up-heaved, leaving Bob feeling overwhelmed by the crushing hegemony of the ordinary life he is surrounded by. Forced retirement, the suppression of his identity, is the obstacle which disrupts the Hero’s “Ordinary World” and Bob’s attempts to conquer it ultimately serve as the catalyst for the rest of the film’s adventures. (Bird, 2004).

The “Refusal of the Call” is Vogler’s third stage, in which the Hero refuses the challenge or journey. Usually, according to Vogler, this is because the Hero is afraid of the unknown, which leads to the Hero trying to turn away from the adventure, however briefly. Alternatively in some cases, another character may express the uncertainty and danger ahead. This stage creates internal conflict concerning the physical quest that lies before the Hero. This contributes to the growing suspense of the story, which is partially relieved when the Hero finally takes up the challenge of the adventure. It also reinforces the familiarity of the Hero as someone who struggles with important decisions just like everyone else. Being too vigorous in taking on the adventure could often seem unrealistic in the mind of the audience and therefore decrease the validity of the story. (Vogler, 2007).

This stage in “The Incredibles” is shown as Bob, despite the energetic encouragement from his wife to suppress his desire to use his abilities and hold down a normal job, reunites with his old super friend, Frozone, to save people from a burning building. Bob’s resistance to being fully ordinary can also be seen at his job at an insurance agency where continues to try to help people by educating an elderly woman concerning the loopholes she can take advantage of in her plan. More obviously it is seen when Bob throws his boss through a number of walls after the boss prevents Bob from stopping a crime. Bob even vocalizes his discontent when he argues with his wife that their son who has super speed, Dash, should be allowed to showcase his abilities by playing sports. These are all clear examples of Bob seeking rebellion against the disruption of the “Ordinary World,” the oppression of being a super, with open displays of power. Bob wishes he could pretend that he still lived in the “Ordinary World,” where he was free to use his abilities. (Bird, 2004). Ironically, Bob’s rebellious refusal to compromise concerning his masculine actions only leads to further emasculation. “To add insult to injury, Mr. Incredible’s diminutive boss fires him from his job… and his wife, the former Elastigirl, assumes the ‘pants’ of the family” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 4).

Another stage is “Meeting the Mentor,” in which the Hero meets a mentor to gain advice or training for the adventure. This mentor is often a seasoned traveler of the worlds who gives the Hero training, equipment, or advice that will help on the journey. However, sometimes this stage can manifest itself as the Hero simply reaching within to a source of courage and wisdom. (Vogler, 2011b). This stage in “The Incredibles” is the introduction of the character Edna Mode, a famous fashion designer who used to design suits for the supers. As such, she is well versed within the realm of supers and their abilities. This certainly contributes to her being thought of as a seasoned veteran. For Bob, Edna furnishes a brand new super suit which he utilizes as he begins to reassume his super persona after being hired by a mysterious woman to stop a destructive robot on her company’s island. Additionally, Edna creates super suits for the rest of Bob’s family, who later in the film use them as they too begin to use their powers. Here we see the seasoned veteran providing the Heroes with the tools they need to be successful. Lastly, it is Edna who advises Helen, Bob’s wife, to follow her husband to the island after she begins to suspect that Bob may be returning to being a super. (Bird, 2004).

“Crossing the Threshold” is another stage in which the Hero leaves the “Ordinary World” and goes into the “Special World.” This most commonly occurs at the end of Act One, when the Hero commits to leaving the “Ordinary World” and entering a new region or condition with unfamiliar rules and values. (Vogler, 2007). We see this stage occurring in scenes in which Bob has tried to put aside what super-masculine role he believes is expected of him to settle down into a normal, ability-free life with an average job. It is present in those first moments when there are no open displays of power. Even when Bob rebelliously uses his powers with Frozone to save people from a burning building, they wear ski masks to hide their citizen identities and their super identities. These are Bob’s first attempts at suppressing his masculine identity as a super and hiding his displays of power from the world. (Bird, 2004).

The sixth stage is called “Tests, Allies, and Enemies.” In this stage, the Hero faces tests, meets allies, confronts enemies, and learns the rules of the “Special World.” In other words, the Hero is discovering his place outside of the “Ordinary World” and is sorting out his allegiances in the “Special World.” (Vogler, 2007). Bob certainly does this in “The Incredibles.” The most influential character that he meets is Mirage, the mysterious woman who encourages Bob to reassume in secret his role as Mr. Incredible. Bob also faces tests in battling the robot on the island, as well as in hiding his activities from others. Finally, Bob encounters Syndrome, the film’s main antagonist. Ironically enough, both Syndrome and Bob share the desire to return to the “Ordinary World,” in which supers live in the open. Although, while Bob wants to help people while simultaneously adding a extraordinary counterbalance to the ordinary things in his life, Syndrome motivations are more concerned with his own renown and glorification. (Bird, 2004).

Another stage is the “Approach” stage, in which the hero hits setbacks during tests and may need to try a new idea.” This describes how the Hero and his newfound Allies prepare for the major challenge in the Special World. (Vogler, 2007). For Bob, preparation for the major challenge occurs as he begins to reassume super activities. However, setbacks arise when Syndrome reveals himself and Bob barely escapes Syndrome’s newly upgraded robot. He makes his way back into Syndrome’s lair, only to be captured. For Helen and two of their children, setbacks occur when Helen begins to suspect that Bob has reassumed his super activities and when, as they travel to the island, their plane is shot down. This is also an emotional setback for Bob, to whom Syndrome reveals the shooting down of the plane. Yet the attack on the plane, in combination with the use of their new super suits and the evasion of guards, actually helps the family prepare for the major challenge. (Bird, 2004). It is in this stage that Bob begins to “embrace his own dependence, both physical and emotional. Trapped on the island of Chronos, at the mercy of Syndrome, … Mr. Incredible needs women – his wife’s superpowers and Mirage’s guilty intervention to escape” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 6). This embrace of the more feminine attribute of dependence also helps Bob prepare for the climax ahead.

“The Ordeal” is one of the more exciting stages, as it is the biggest life or death crisis. This occurs near the middle of the story, as the Hero enters a central space in the “Special World” and confronts death or faces his or her greatest fear. Often during this scene, out of the moment of death comes a new life. (Vogler, 2007). In “The Incredibles,” this stage occurs on the island in the rescue of Mr. Incredible and the family’s battle to escape from the island. During this challenge each of the characters learn even more about their powers and learn how to work together as a team. Their escape is an epic fight against the minions of Syndrome and the lives of each character are certainly in danger, forcing them to confront fears of death and also Bob’s fear of losing his family. In working together for the first time, the characters realize the strength of their family bonds and by the end of the scene we see the “birth” of the Incredibles as a unit, as opposed to separate individuals. (Bird, 2004). This initial success through teamwork foreshadows the ultimate shift in from independent masculinity that Mr. Incredible encounters later in the film.

“The Ordeal” leads to the realization of “The Reward,” in which the Hero takes possession of the treasure won as a result of surviving death and overcoming fear. Vogler describes how there may be a celebration, but there is also the danger of losing the treasure again. (Vogler, 2007). “The Rewards” gained by the Incredibles is safety the reunion of the family. After escaping the island, there are no longer any forces keeping them apart or endangering them specifically. Additionally, Bob has achieved his “Reward” of being a super once again. However, despite joy in their victory, the Incredibles can take little time to celebrate, as Syndrome has released his robot upon civilization. (Bird, 2004).

This leads to the stage called “The Road Back,” in which the Hero must return to the “Ordinary World.” This normally, according to Vogler, occurs three-fourths of the way through the story as the Hero is driven to complete the adventure; leaving the Special World to be sure the treasure is brought home. Vogler points out that often a chase scene signifies the urgency and danger of the mission. (Vogler, 2007). This is a stage clearly apparent in “The Incredibles,” as the family rushes back to society in order to save lives from the actions of Syndrome and his robot. (Bird, 2004).

Once back in the city, the Incredibles face “The Resurrection,” Vogler’s stage in which the Hero faces death and is forced to use everything he has learned. In other words, it is a climax at which the Hero is severely tested once more on the threshold of home. Often, the Hero is purified by a last sacrifice, another moment of death and rebirth, but on a higher and more complete level. By the Hero’s actions, the polarities that were in conflict at the beginning are finally resolved. (Vogler, 2007). In “The Resurrection” stage, the Incredibles each have to use their newly developed skills, including working together as a team and utilizing information learned in their adventures, in order to defeat Syndrome’s robot. As Vogler describes, this scene happens in the home city of the family. (Bird, 2004).

Mr. Incredible’s ultimate realization that he can no longer succeed on his own, but now needs others, contributes to his final shift in masculinity. “To overpower the monster Syndrome has unleashed on the city, and to achieve the pinnacle of the New Man model, he must also admit to his emotional dependence on his wife and children” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 6). Mr. Incredible makes one last attempt to refuse his emasculation by hiding his family in a bus, but even his confessed reasons for doing so have altered. He lovingly admits to Elastigirl that “I can’t stand to lose you again,” which stands in sharp contrast with is ideology at the start of the movie: “I work alone” (Bird, 2004). However, his family does not stay hidden for long; he needs them to finally vanquish the robot. Yet when the robot is destroyed, so too are “any vestiges of the alpha model, as the combined forces of the Incredible family locate a new model of postfeminist strength in the family as a whole. This communal strength is not simply physical but marked by cooperation, selflessness, and intelligence. The children learn that their best contributions protect the others” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 6). Thusly Bob completes his character arch, reflective of the shifting face of masculinity in cinema. As Hansen-Miller says, “While the hero can be traumatized by the burden of their abilities and the sources of their power they are ultimately heroic and justified by reassigning those abilities to a fight for heterosexual love and family” (Hansen-Miller, 2010, p. 38).

The “Return with the Elixir” stage describes the Hero’s return home from the journey where he uses the “Elixir” to help everyone in the “Ordinary World.” Vogler details how often the transformation of the “Ordinary World” as a result of the “Elixir” often mimics the transformation that the Hero has undergone throughout his adventure. In “The Incredibles,” the return of supers and their abilities is the “Elixir” that is presented to the “Ordinary World.” Just as Bob realizes how important his family is to him, the people of the city, whom they have saved, realize how important the supers are to them and their city. (Bird, 2004).

In summation, Bob is a super living in an “Ordinary World,” in which supers are respected and appreciated and he, as Mr. Incredible, can accomplish great displays of power, which provide for him an extraordinary counterbalance to the ordinary things in his life. However, the forced retirement of supers creates a “Special World” in which supers cannot be heroes who accomplish great things. This is a “Call to Adventure,” as it represents a direct challenge to Bob’s identity and purpose. Bob initially “Crosses the Threshold” into this “Special World” and lives the stereotypical American Dream, with a steady job and no phenomenal feats of strength. However, Bob “Refuses the Call” to retire and secretly, yet defiantly, takes part in displays of power. Bob’s struggle to overcome what he perceives as the suppression of the “Special World” brings him into contact with Edna, a “Mentor” who prepares him for the resumption of super work, and Mirage, an “Ally/Enemy who provides him with the opportunities of “Tests” through which he can be a super once more. The “Approach” to the film’s climax involves Bob being captured by Syndrome, an “Enemy,” and the rest of the Incredible family making their way to the island to find Bob. In the “Ordeal,” Bob is rescued and the family escapes the island, learning about their powers and how to work together along the way, and they achieve the “Rewards” of being reunited as a family and being able to reach their potential as supers. Yet they quickly take the “Road Back” in order to defeat Syndrome’s robot in the “Resurrection” stage, in which they must use everything they learned along the way in order to succeed. This leads to their “Return with the Elixir,” which manifests itself in the film as the return of the supers and their abilities, and also to the return of the “Ordinary World,” in which the story began.

Using “The Hero’s Journey,” the creators also presented an insightful look into the changing face of masculinity in the cinema. Bob starts the film reflective of the classical masculine heroes of the eighties and nineties. However, his masculinity that was once so applauded eventually led to his emasculating downfall. In order to reestablish himself as a super, Bob ultimately renegotiated his masculinity as he was forced to accept the help of others, including women. However, this is a role that Bob finally accepts and it is viewed as a more ideal form of masculinity than that with which Bob began the film. This shift in cinematic masculinity, represented in “The Incredibles” by Bob, is explained by Hansen-Miller when he states that “the attempt to reconstruct masculinity outside of historical homosocial value systems indicates recognition of female audiences and agency” (Hansen-Miller, 2010, p. 38). Gillam and Wooden concur, saying “The trend of the New Man seems neither insidious nor nefarious, nor is it out of step with the larger cultural movement. It is good… to be aware of the many sides of human existence, regardless of traditional gender stereotypes. However, maintaining a critical consciousness of the many lessons taught by [movies]… remains a necessary and ongoing task… for all conscientious cultural critics” (Gillam & Wooden, 2008, p. 7).

“The Incredibles” certainly offers itself for such analysis, as it effectively uses “The Hero’s Journey” to provide a clear example of the changing face of masculinity in film.

Works Cited

Bird, Brad (Director). (2004). The Incredibles [Motion Picture]. United States: Pixar Animation Studios.

Campbell, Joseph. (2008). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gillam, Ken, & Wooden, Shannon R. (2008). Post-Princess Models of Gender: The New Man in Disney/Pixar. Journal of Popular Film & Television, 36(1), 2-8. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

Hansen-Miller, David. (2010). “Iconic masculinities, popular cinema and globalization.” Media Development, 57(1), 33-38. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

“The Hero’s Journey.” ThinkQuest. (2011). Retrieved from <http://library.thinkquest.org/03oct/00800/journey.htm>.

“The Incredibles.” IMDb. (2011). Retrieved from <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0317705/>.

Kahn, Jack S. (2009). An Introduction to Masculinities. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Seton, M. (2008). Pixar Phenomenology: The Embodiment of Animation. (cover story). Metro, (157), 94-97. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

Vogler, Christopher. (2007). The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Vogler, Christopher. (2011a). “A Practical Guide to Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces.” The Writer’s Journey. Retrieved from <http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero%27s_journey.htm#Practical>.

Vogler, Christopher. (2011b). “The Hero’s Journey Outline.” The Writer’s Journey. Retrieved from <http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero%27s_journey.htm#Hero>.

Vogler, Christopher. (2011c). “The Heroine’s Journey/Archetypes.” The Writer’s Journal. Retrieved from <http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero%27s_journey.htm#Heroine>.

Vogler, Christopher. (2011d). “The Memo that Started it All.” The Writer’s Journey. Retrieved from <http://www.thewritersjourney.com/hero%27s_journey.htm#Memo>.

No comments:

Post a Comment